The typical age range during which ear infections are seen is from 6 to 15 months old. Symptoms range from mild pain to hearing loss and brain abscess. There are three areas that become infected in the ear, and to understand this requires some knowledge of the anatomy:

The external or outer ear is where otitis externa (OE), also known as swimmer's ear, occurs. This is is the only infection that causes pain with manipulation of the ear. The outer ear will usually be red and tender the the touch. The most common cause of this is a bacteria called pseudomonas, which thrives in wet conditions. The treatement for this, therefore, is over the counter ear drops that dry out the ear canal and make the area uninhabitable for the bacteria.

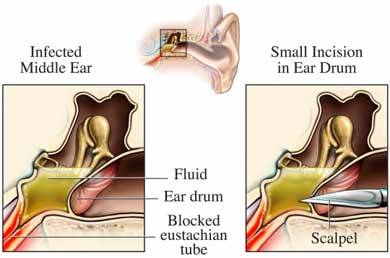

The middle ear is behind the eardrum or tympanic membrane. It is the space that houses the ear ossicles, the bones which transmit sound from the eardrum to the cochlea of the inner ear. This area is connected to the back of the nose (pharynx) via a hollow tube known as the eustachian tube. An infection of this space is known as otitis media (OM). There are different types of OM, depending on the length of time it has persisted and whether or not fluid (effusion) is present.

Acute otitis media (AOM) typically occurs in <2 years old, usually caused by viruses such as RSV, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu) but can also be due to bacteria. Mucosal congestion caused by the upper respiratory infection (URI) is aspirated up into the middle ear where inflammation occurs.

Treatment: If younger than 2 years old, an antibiotic such as amoxicillin will be prescribed. If older than 2 years old, doctors may choose to wait 48 hours to see if symptoms improve on their own before deciding to add an antibiotic. This is because studies have shown spontaneous resolution (without treatment) in up to 80% of this age group in 2-14 days.

Otitis media with effusion (OME) occurs when bacteria gets into the middle ear and fills it with pus. In growing children less than 7, the eustachian tube is often short and less vertical, so pus cannot drain properly and begins to back up. This growing pocket of fluid causes a large amount of pressure and pain to the child. The doctor will use a pneumatic otoscope to blow a burst of air at this ear drum. Normally the ear drum will move but in the case of OME, no movement occurs. Tympanometry may also be used to determine this. Long term OME (>3 episodes in 6 months or >4 episdoes in 12 months) may lead to hearing and language problems, so treatment is often indicated.

Treatment: myringotomy (hole is cut into the ear drum) with tympanostomy tube insertion is surgically performed. This allows fluid to freely drain out of the ear instead of backing up. It also alows antibiotic drops to be placed in the ear, which move through the tube and into the middle ear space to treat bacterial infections. Parents are instructed to apply the drops for 10 days whenever they see pus draining from the ears, which allows them to treat infections at home.

Reference

American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media with Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics 2004; 113(5): 1412-29.